BOX (2018)

poster boards, spray paint, duct tape, clear plastic wrapper, hair brush, person, tank top, shorts

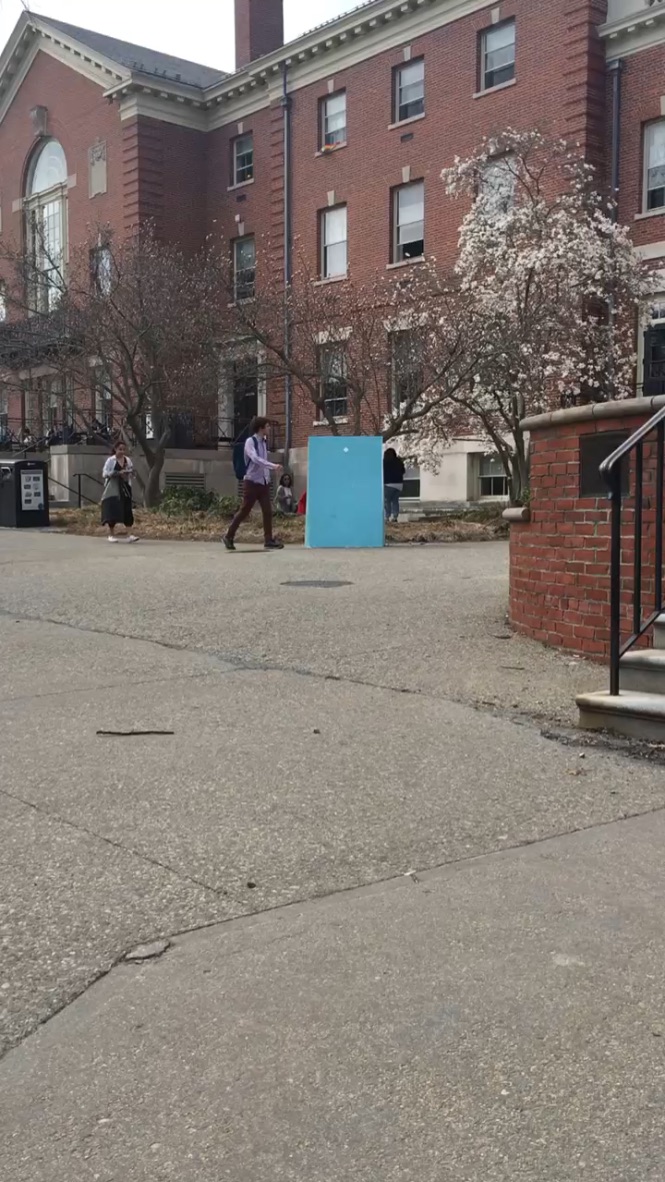

5’ x 3’ x 3’

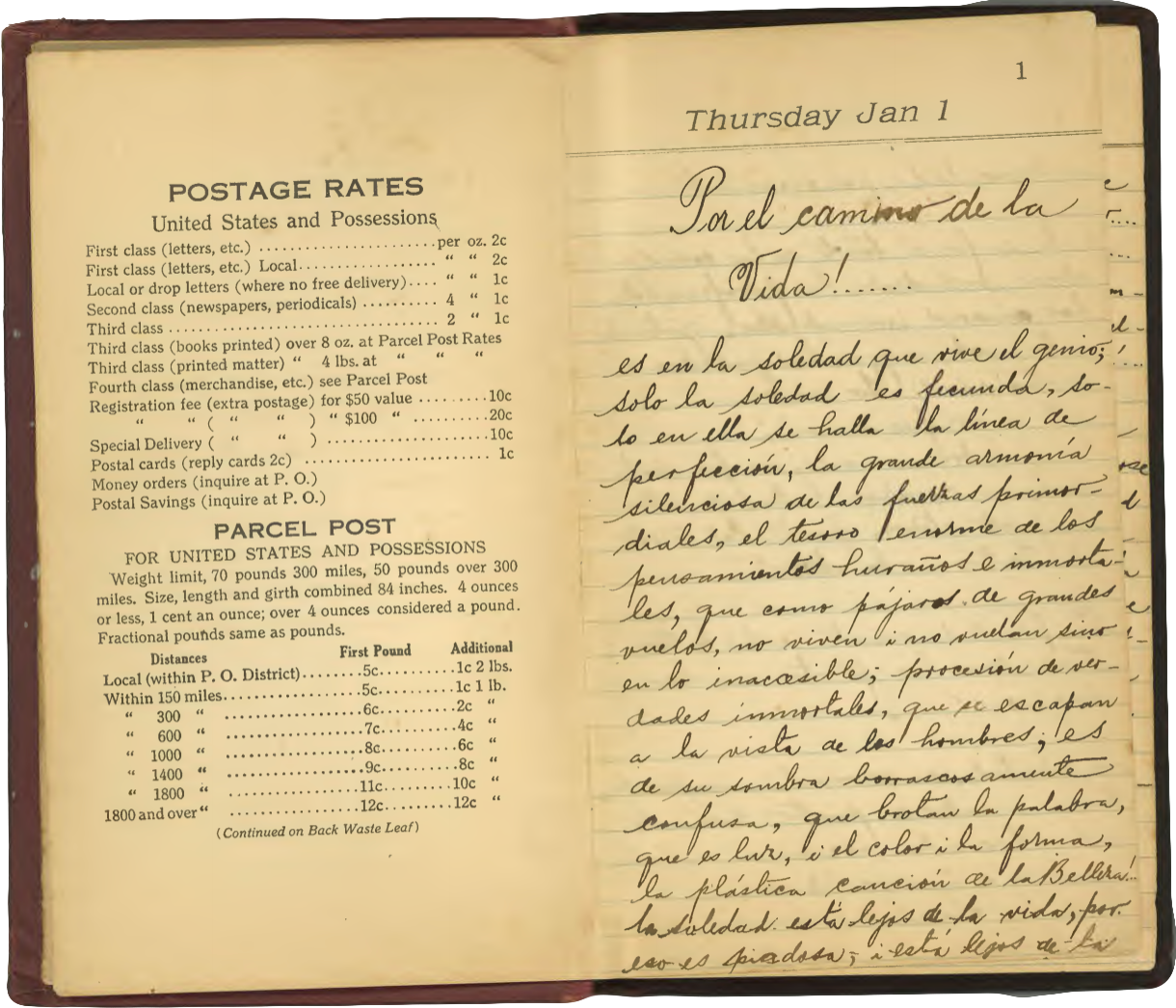

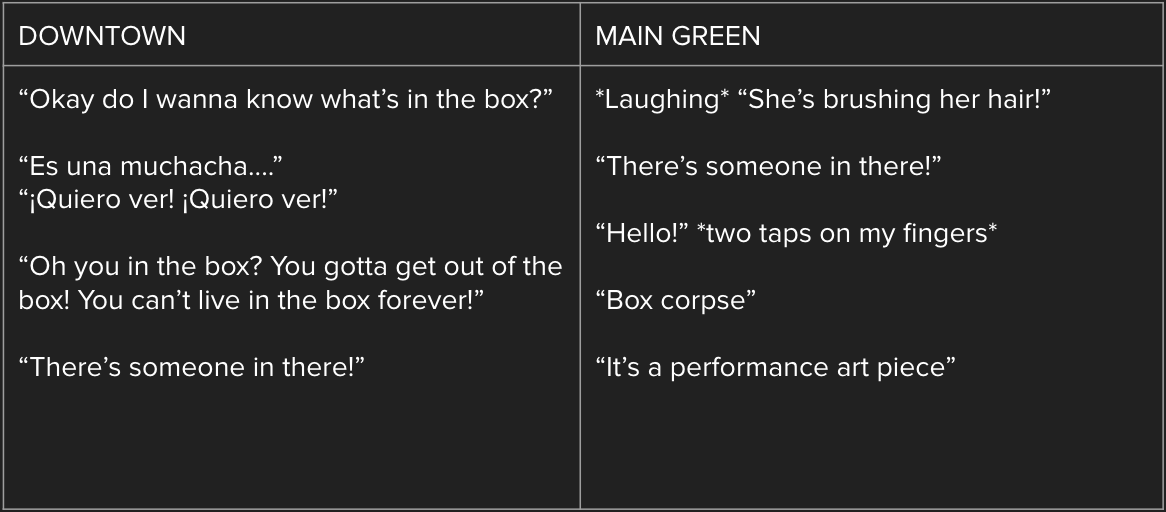

Peformed in May 2018 at Kennedy Plaza in downtown Providence and at various locations on the Brown University campus, BOX is a performance in which I sat in a large blue box and brushed my hair, eyes cast down, while passersby could approach to watch through an eyehole.

Spring 2018

BACKGROUND

French colonizers were frustrated by Algerian women’s ability to look at them through their burkas while maintaing invisibility themselves behind their clothing. So the French took to unveiling Algerian women as a means to correct the power imbalance they perceived in the visual dynamic between colonizer and colonized. In Mulvey’s theory about the male gaze, the act of seeing creates a power structure in which the one looking is a subject and the one being looked at is an object. Furthermore, Simone Browne’s writing on surveillance and sousveillance describes about how Black servants in the US were supposed to avert their eyes from the white people they served. To understand the gravity of the seeing act, we need look no further than the murder of Emmett Till, in which an alleged glance at a white woman was justification enough for those who lynched him.

These days, looking has taken on new forms through social media. Screens have allowed people to look at others without their knowing. Someone asks you, “Do you know Jerry?” You respond that the name rings a bell, but you can’t put a face to it. They instantly pull up a picture of Jerry from his social media accounts. The ability to look at others on social media can quickly devolve into unhealthy habits, for instance, stalking an ex or chronic comparison to others.

People can see others virtually whenever they want without anyone having to know that this act of looking is taking place. Now more than ever we can gaze upon others (on our screens) without needing to actually engage with them.

Social media has also given the public access to our private lives. Thus, former divisions between the public and private self have blurred. This blurring is not inherently bad or good, but by acknowledging this shift, as BOX intends, we might better understand how our ways of relating to one another are transforming. Making visible traditionally private moments can be empowering, connective. It can erode harmful taboos. Increased inter-visibility is restructuring the social sphere of the twenty-first century in manifold interesting ways.

In BOX, I re-contextualized this virtual, visual interaction in physical, public space, where everyone is a potential witness to the glances of others. By taking the everyday digital act of looking at another person who is not looking back at you and bringing it into a live, in-person, and thus more vulnerable context, I hoped to amplify the feeling that the act of looking evokes. I wanted to give people the experience of gazing at someone who is not reciprocating their gaze, but who is in the same physical space as them, and who has the potential to notice their gaze. By putting myself in a public space but acting in a private way, people could have the unexpected experience of rendering a person into a spectacle, a subtle act carried out in the instance of their looking.

The performance was also a social experiment, as it implicated viewers in a social dynamic with the allure of a mysterious large blue object entering public space, and the surprise, once they looked through the box’s plastic peephole, of a privatized sentient human being less than a foot away from them becoming the clear object of their public gaze.

I believe in the accessibility of art to the public, visible and tangible not just to those who enter intentionally into spaces with art on display, and not just to the Brown University community.

PERFORMANCE

I hoped to steal the attention of passersby away from the blue-lighted rectangles of their smartphones to the light blue rectangle of the box’s façade.

I cut a peephole around eye level and put a piece of plastic behind it to create a transparent separation between the public and me, inside the box. The separation contrasts the distance and anonymity in online visibility with the realness of my live body inside the box. In order to appear more vulnerable and therein reflect the private sphere, I wore a beige tank top and black shorts and brushed my hair in the box— a private activity, usually carried out in one’s bedroom, often alone.

I chose a mundane and un-extraordinary activity, sitting and calmly brushing my hair, to carry out in the box in order to focus on the “simple” act of seeing. People’s reactions would be triggered then not by some shocking spectacle hidden within my enclosure but rather by the feeling elicited when they found themselves looking at someone who was clearly not looking back at them.

Some things I heard:

REFLECTIONS